Moneyballocracy

"Predictions are hard, especially about the future" - Neils Bohr, possibly apocryphally

(Adapted from a talk I gave at Yale this month as part of the annual International Workshop on Reimagining Democracy; thanks to Bruce Schneier & co. for the invite.)

A brief history of prophecy

One fine day in 1907, 787 attendees of a livestock fair guessed the weight of a prize ox. Francis Galton analyzed their guesses, and discovered that while none were correct, the average guess was within 1% of the correct weight. Thus was born the notion of the “wisdom of the crowd” — that collective estimation tends to be better than individual guesses.

Years later, Philip Tetlock et al showed that this was also true of predictions (unsurprisingly; predictions are just estimations of the future) but also, interestingly, that a small number of people are consistent “superforecasters,” who outperform not just the wisdom of the crowd, but even experts who better understand the domains in question. (Famously, in a head-to-head comparison, superforecasters performed 30% better than CIA analysts with access to classified information.)

Since then several online platforms have sprung up to try to collect and collate predictions of the future, in domains ranging from geopolitics to AI to sports. The best known are “prediction markets” such as Manifold, Kalshi, and Polymarket, where users bet against one another. From 2023-24 I worked at a more rigorous and academic platform, Metaculus, which does not pit users against one another as counterparties, but simply collects and scores their individual forecasts.

I worked there because it was the most science-fictional job I could find. The prospect of better predictions of the future stirs inspiring, if handwavey, prospects: what if we could predict wars and pandemics, and/or even head them off? Or, for that matter … what if we could predict victorious electoral candidates?

The present of prophecy

It is fair to say forecasting is having a moment. Earlier this month Kalshi raised $1 billion, with a B. A few months ago Polymarket raised $2 billion1.

Prediction markets aren’t quite the same as pure forecasting — my former colleague Ryan Beck has written an excellent piece comparing & contrasting their pros & cons — but they are still a legitimate form of it. (Of note, they can support conditional forecasting, i.e. of the form “If X happens, what is the probability that Y happens?” although the popularity / liquidity of such markets tends to be low.)

One might look at recent events and think “billions of dollars! an explosion of interest! forecasting is an exciting new industry in the midst of an extraordinary boom!” On paper, one wouldn’t be wrong...

The reality of prophecy

…but in practice, let’s not kid ourselves: as Matt Levine has documented at exhaustive and entertaining length, modern prediction markets are basically a fig leaf for semi-hemi-demi-legal-ish sports betting. (They get away with this because they are, hilariously, currently ‘regulated’ as commodity futures exchanges!)

Even if we pursue the nobler handwavey goals, remember: we did forecast COVID, and nobody cared. (Instead people, even journalists, got big mad.) Internal corporate prediction markets have been unsuccessful, even at Google, where they seemed to fit the corporate culture well. (The jury is out on Anthropic’s.)

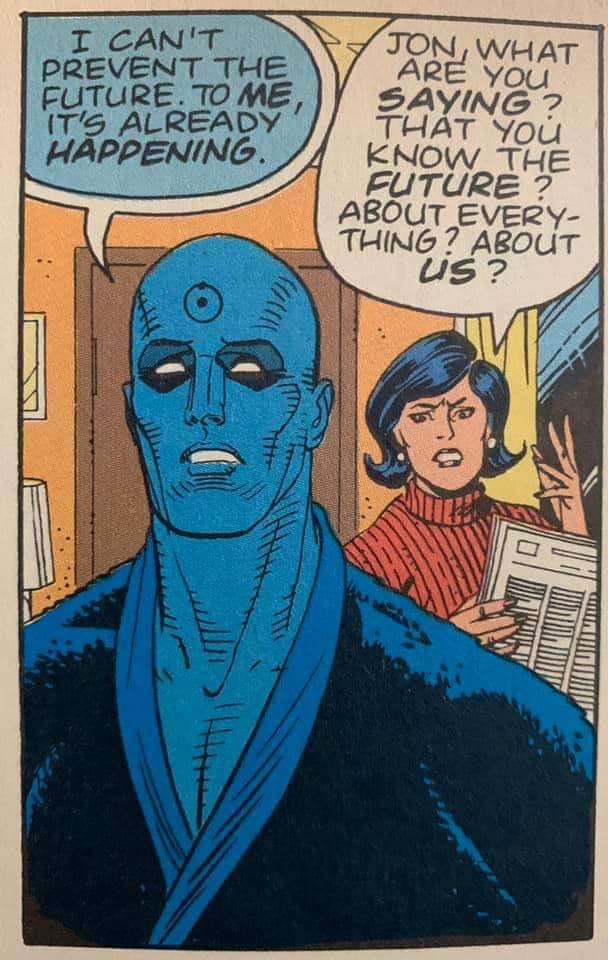

Indeed one quickly learns from working in forecasting that it is surprisingly difficult to make money from better predictions of the future. Superforecasters are not Hari Seldon or Cassandra; rather they are somewhat more accurate, most of the time. This makes it easy to rationalize rejecting their predictions.

You can really only glean a significant advantage from superior forecasting in fields where being a bit better matters a lot. You might think “aha, alpha!” — but financial firms already hire superforecasters2, they just call them “analysts.”

And now for the least surprising twist in my entire oeuvre

…And then AI entered the chat.

I was at Metaculus when GPT-4 launched, and the only person there who thought it might be good at predictions. (Not because I was a good forecaster. In fact I was the worst forecaster at both of the forecasting companies I worked at, which is a little embarrassing; I blame my unfortunate habit of writing science fiction. Instead I thought this because I’d gotten a sneak peek of GPT-4 some months earlier.)

Metaculus scores forecasts rigorously, and has shown GPT-3.5 to be no better at predicting the future than random guesses. But GPT-4 was significantly better; and as models have gotten better, so have their forecasts. A startup named ManticAI ranked eighth in this summer’s Metaculus Cup, and is currently seventh in the active competition (which closes Jan 1.) This trend is probably kind of a big deal.

I like to think I was one key reason Metaculus now hosts AI Forecasting Benchmark Tournaments (at least, I believe I was the first to suggest it, though it launched after I left the company.) While the results of the latest tournament, which pits bots against pro forecasters, show that the pros still “significantly outperform bots,” it’s worth noting:

these bots are mostly hobby projects

they already rival and sometimes exceed the “wisdom of the crowd.”

they’re clearly getting better, and will continue to do so — “the most important factor for accurate forecasting is the base model used.” (When this latest tournament ran, the state of the art was OpenAI's o3. If you’re in the AI biz, o3 seems like a very long time ago already … but by their nature, prediction tournaments tend to occupy a lot of wall-clock time.)

Plenty of other data points concur that AI forecasting is a very real thing already, and while AI can’t yet surpass human superforecasters, it’s beginning to feel like a matter of not-all-that-much time.

The perils and promises of superhuman forecasting

I subsequently worked at an AI forecasting company named FutureSearch, which consisted largely of fellow ex-Metaculites; its CEO Dan Schwarz was Metaculus’s CTO. FutureSearch combines AI engineering with superforecasters to create some remarkable research tools. “Superhuman forecasting” may sound implausibly starry-eyed, but if “superforecasters plus exhaustive AI research3” are better than “superforecasters alone” — and those I worked with sure seemed to think so! — then we’re already in an era of superhuman forecasting.

Will / when will we get to autonomous superhuman forecasting? It’s hard to say. To massively oversimplify, good forecasting requires good research, a good world model, and insight. LLMs famously don’t seem to have good world models (yet), but they are much better at research than casual users appreciate, if you’re willing to spend a lot of tokens. We live in a world ever more awash in researchable data.

But we already have autonomous superhuman forecasting when it comes to scale. FutureSearch4 offers forecasts for every publicly traded stock in the US, otherwise wholly impractical without a massive army of analysts. The supply of superforecasters is very limited; it’s not practical to get them to generate, say, weekly arrays of county-level conditional forecasts for all of the 3,000 counties in the USA. But it is practical, and more cost-effective than you might expect, to generate AI forecasts — whose quality already rivals the wisdom of the crowd — at that scale.

Moneyballing democracy

Another field where being a bit better matters a lot is, you may have noticed, elections.

Today we try to make voters’ intentions legible in advance through polls, but polling has many practical limitations, and is a snapshot of an electorate whose views will evolve over time. (Sometimes in obviously predictable ways, such as presidential elections’ “convention bounce.”) Conditional polling — “if X, how would you vote?” is even more limited.

AI forecasting does not have those limitations. Modern LLMs could run arrays of dozens of conditional forecasts for every county in the USA, weekly — and cheaply, compared to the amount spent on American elections — on conditions like:

If candidate X runs vs. candidate Y, how will people vote?

If we convey message Q vs. message Z, how will people vote?

If our platform includes proposal A vs. not including it, how will people vote?

If these forecasts have any validity — and given all the above, there seems to be good reason to believe that they will — the democratic consequences will be non-trivial.

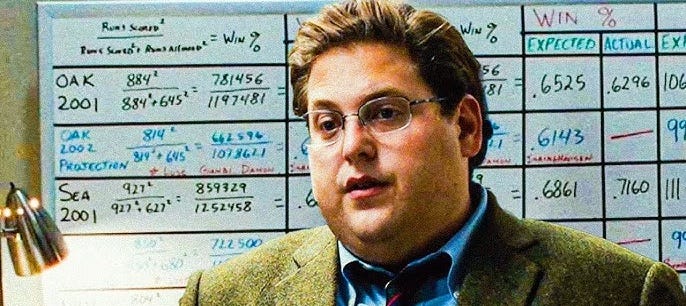

The movie Moneyball is ostensibly about baseball, but it is really a paean to statistical analysis. It tells a tale of quantified legibility competing with and rapidly surpassing the “instincts,” “eye tests,” “gut feeling,” “long experience” of the previous era. It happened fast; Moneyball is already something of a historical artifact in that, for better or worse, almost everyone in sports is a sabermetricist now. This is an arc we should expect to see more of over the coming years, as AI forecasting makes the future (somewhat) more legible.

Not all of the possible consequences are good. On one hand, this increased legibility could be used to reinforce democracy by helping to select candidates and issues which reflect what communities actually want. On the other, it could be grossly misused for cynical manipulation of the electorate. Either way, though, if only one side of a polarized democracy makes use of this newfound legibility, that will be a major electoral advantage … whether we like it or not.

Food for thought, as AI models keep getting better, and we head into the next set(s) of highly consequential elections worldwide…

But fear not, I am not likely to be biased here by my (estimated) 0.05% ownership of Metaculus; it’s a public benefit corporation and in no way a betting platform, which is where the money is.

Bridgewater partners with Metaculus explicitly to find talented people to hire.

to forestall knee-jerk objections from those outside the industry; yes, LLMs hallucinate. No, this is not an unsolvable problem, just an annoying and sometimes expensive one.

I own 0.00% of FutureSearch, btw, having been poached by Meta Superintelligence before any of my options vested, so there is no financial bias to my talking them up here.