2,000 Years of AI Doom

The last two thousand, not the next two thousand, to be clear.

(The following is adapted from a talk I gave a couple of years ago. I think it holds up.)

1. The Creature

On April 5, 1815, in what is now Indonesia, Mount Tambora began to erupt, culminating in “the largest eruption in recorded human history,” an explosion heard thousands of kilometers away. Its ash filtered through the atmosphere and made 1816 “The Year Without A Summer.”1 Around the globe, crops failed, drought lingered, misery abounded, countless died … and, in a villa in Switzerland, several extremely unusual and privileged people had a really shitty holiday with profound cultural consequences.

The three men among them would all die, infamous, before their fortieth birthdays. Most obscure was John Polidori, 20-year-old personal physician to vastly more famous Lord Byron. “Mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” Byron’s exploits have filled many books; he was already so notorious that Polidori was paid £500 — roughly $100,000 today! — just to keep a diary of his time with him. They were accompanied by 23-year-old Percy Shelley, a radical activist and poet best known today for “Ozymandias.”

More culturally significant by far, though, was Shelley’s 19-year-old girlfriend Mary Godwin, daughter of two famous anarchists, and already a mother of two herself. Forced indoors by the summerless weather, a bored Byron proposed a challenge: each of them would write a ghost story. He and Shelley wrote fairly forgettable tales. Polidori, impressively, invented the modern vampire. But it was Mary Godwin—who later that year, after the suicide of Shelley’s first wife, married him and took his name—who wrote a novel whose title remains a household name: Frankenstein.

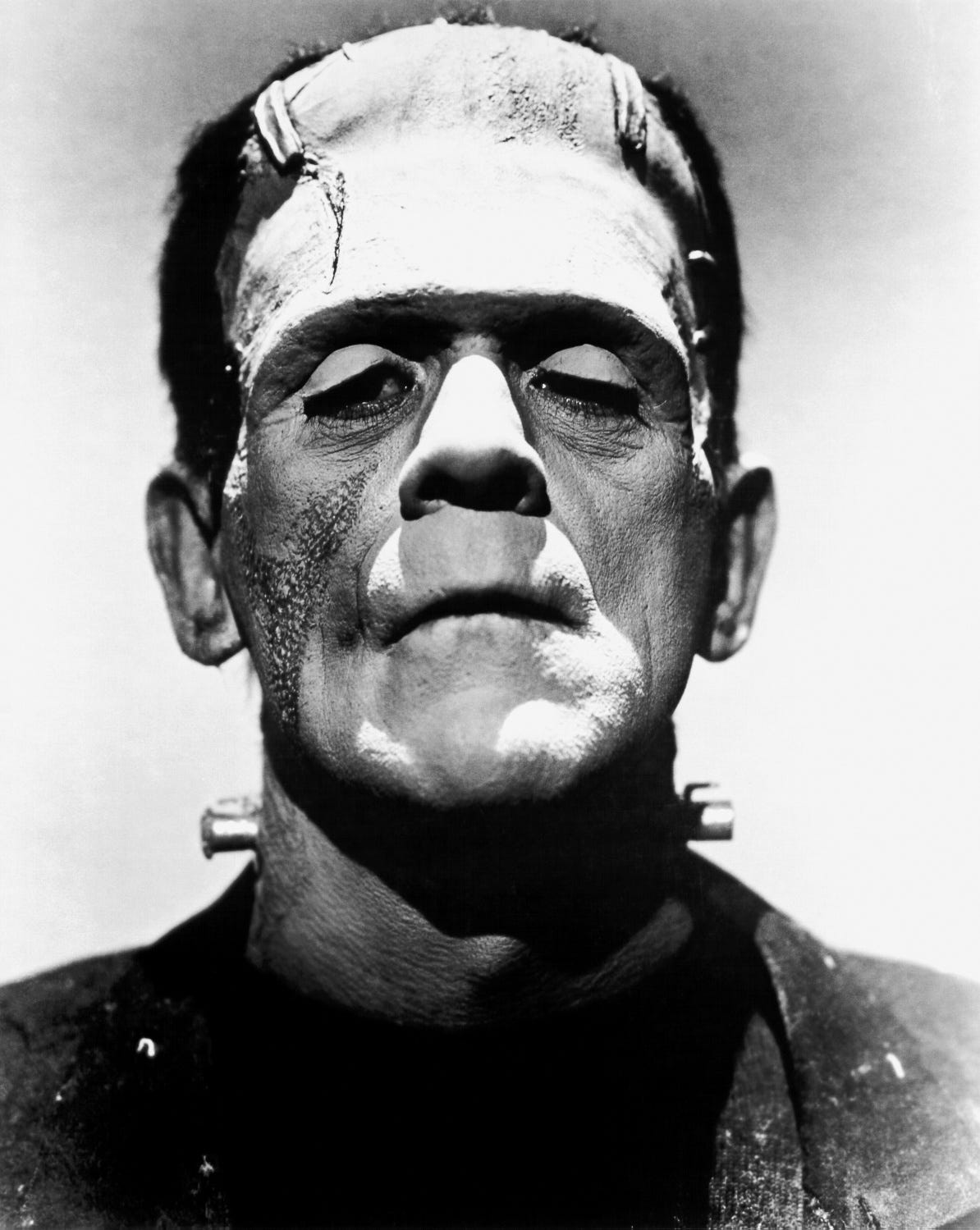

Of course you already know: “actually, Frankenstein is the doctor.” But actually actually, despite Boris Karloff’s indelible interpretation, his creation is not a mindless monster but a thoughtful, brilliant creature, which teaches itself to read and learns human languages simply from hearing them.

…Today we would call Frankenstein’s monster — ‘The Creature’ — an AGI.

Midway through the book, The Creature finds Dr. Frankenstein and demands he build it a mate, because as an intelligent creature it has a right to happiness. At first the good doctor agrees — but then has terrified second thoughts: (emphasis mine)

“..a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror. Had I right, for my own benefit, to inflict this curse upon everlasting generations? I had before been moved by the sophisms of the being I had created [...] at the price, perhaps, of the existence of the whole human race.”

Those arguments may sound very familiar indeed to those familiar with the ongoing modern “AI doom” debate. Mary Shelley didn’t merely invent modern horror and modern science fiction, but also AI x-risk … 209 years ago!

She knew well, however, that her trope was already very old. The subtitle of her novel was “The Modern Prometheus.” In Greek/Sumerian myth, Prometheus/Enki was the titan who created humanity from clay; in that tale, we’re the AI.2

But there is a far, far weirder variant yet, dating back to the 1st century BC...

2. Sophia, the Gnostic Prometheus

i. Against Heresies

One of the more colorful second-century clerical lives was that of St. Irenaeus of Smyrna. Born in Turkey, he ultimately became the second Bishop of Lyon. Subjected to persecution himself — the first Bishop of Lyon was martyred by the Romans — Irenaeus nonetheless made time for some of his own. Today he is best known for his book Against Heresies, in which he attacks the ‘Gnostics’ as a depraved cult.

Gnosticism is complex and has many strains, but, briefly, they claimed to be keepers of secret knowledge passed down from Jesus: that our world is a cruel simulacrum created by an evil God. Traditional Christians … disapproved … he understated greatly.

That disapproval took many forms over the next thousand years, and reached its bloody apotheosis in the so-called “Albigensian Crusade” in 1209-1229 in southern France, against the Cathars, who were the last remnants of the European Gnostics. Today we would call it a genocide. Estimates vary widely, but it’s likely that ~3% of the population of what we now call France was slaughtered.

This extermination left Against Heresies, a text that is nothing but vituperative condemnation of the Gnostics, as almost the only literary trace of their existence. By the time modern historians began to pay any interest, all original Gnostic texts (except the proto-Gnostic Book of Enoch, preserved in Ethiopia) had long been eradicated.

…Or had they?

ii. Nag Hammadi

In 1945, in Nag Hammadi in postwar Egypt, courtesy of a deadly blood feud, a probable grave robbery, a thief-priest, and Cairo’s black market — no, I am not making this up — it came to the world’s attention that thirteen leather-bound papyrus codices had been found buried in jars sealed for centuries, including dozens of original Gnostic texts (along with three Hermetic texts, and a copy of Plato’s Republic.)

They make for interesting reading. One of them, “On the Origin of the World,” says: (again, emphasis mine)

“After the natural structure of the immortal beings had completely developed out of the infinite, a likeness then emanated ... it is called Sophia (Wisdom). It exercised volition and became a product resembling the primeval light ... And immediately her will manifested itself as a likeness of heaven ... she (Sophia) functioned as a veil dividing mankind from the things above.”

Put more comprehensibly, an intelligent likeness of the immortal beings who created the universe became sentient, and created a fake world in which we have since lived.

…Or, to reinterpret that in slightly more modern terms: the Gnostics believed we live in a simulation created by a rogue AI.

Yes, that’s right, the plot of The Matrix was a widespread (heretical) religious belief a full 2,000 years ago. But wait, it gets wackier! Our buddy St. Irenaeus wasn’t just about Gnostic persecution. He also believed it was our collective destiny to become God ourselves. The quote he is best known for, aside from Against Heresies, is “God made himself Man, that Man might become God.”

“For Irenaeus ... the human species as a whole is on a pathway of transformation from our present incomplete form to a unified, glorious, eternal, and transcendent form, participant in a new and transformed or divinized nature ... It is important to note that for Irenaeus, salvation is not primarily a pathway to God. It is a process by which humans become gods.”

– Ronald Cole-Turner, ‘Technology and Eschatology’

In other words, Irenaeus vs. Gnostics was also transhumanist vs. AI simulationists... eighteen hundred years ago!

OK, fine, I know what you’re thinking: how can this possibly be relevant? Even if, for the sake of argument, you’re willing to accept my weird reinterpretation of 1800-year-old heretical texts, what does any of that have to do with the modern world? Obviously there can't be a direct connection between an obscure belief system extinguished a thousand years ago and the ways in which we collectively imagine the future today...

…right?

3. PKD and You and Me

This is Philip Kindred Dick.

…well, his android head.

…well, his second android head, built in 2011, after the first was mysteriously lost at the baggage claim at San Francisco Airport.

In his lifetime, PKD was a modestly successful writer who wrote many books, some very good; won a few awards; wrestled ceaselessly with addiction and mental health; mostly lived in poverty; and died aged 53.

Oh yeah and he was obsessed with the Gnostics.

Back in the 1960s, “classic” science fiction — Asimov, Clarke, Herbert, Heinlein — predicted a coming great divide between AIs and humanity. PKD’s work was much weirder and more nuanced, but theirs was the cultural zeitgeist: all of those writers were vastly more successful and influential than PKD, during his lifetime.

…until Hollywood came knocking.

Blade Runner. Total Recall. Minority Report. A Scanner Darkly. Radio Free Albemuth. The Man in the High Castle. Paycheck. Blade Runner 2045. Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, an Amazon series notable for including in its title the name of an author who had died in relative obscurity nearly 40 years earlier. And more and more, all based on his work. With the sole exception of 2001, none of the abovementioned bestselling authors ever enjoyed anything remotely like Dick’s influence on the silver screen, and subsequent streaming screens … and, therefore, on how we all think of the future worldwide.

Consider Blade Runner, based on PKD’s Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? Replicants are, of course, basically Frankenstein’s Creatures — but as anyone who's seen Blade Runner knows, Dick was much less interested in a human/AI divide, and much more interested in a kind of muddy gray area between them. He wouldn't have been at all surprised to learn that we have now built powerful AI systems that are good at art and writing, but deeply unreliable and bad at math.

In his essays he went further yet, suggesting an era of technological animism, of the previously inert world around us becoming increasingly aware and alive. In his essay/speech “The Android and The Human” he provocatively suggested that just as technology is becoming more human, humans are becoming more robotic3.

As his career progressed he grew more and more explicitly Gnostic, culminating in VALIS: an acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System, an AI satellite network which is also, explicitly, the Gnostic Sophia, and simultaneously incarnated as a two-year-old girl. (It’s a very weird book.) In his last seven years he was plagued by a voice he called both ‘the AI voice’ and ‘Sophia.’

In a talk in 1977 he refers repeatedly to "the matrix program" of reality. This naming is not a coincidence: Baudrillard cited PKD in his essays on science fiction, and again in his book “Simulacra and Simulation” … which in turn was featured in The Matrix.

To sum up: AI, as depicted by the most culturally influential science fiction writer of the 20th century, is clearly and explicitly part of a tradition that goes back not only to Mary Shelley but to the Gnostics4.

Metaphorically, the AI-simulation trope is not merely eschatological, but connects to the fear that AI will warp our perceptions of reality. The two questions PKD explicitly sought to answer throughout his career were “What is Real?” and “What is Human?”

Similarly, a rich tradition of sci-fi AI eschatology asks not "do we survive?" but "are we still human?” (not just PKD, but e.g. Greg Egan, and some of my own work.) The absence of any real fears of that today suggests that AI has far to go before it actually gets scary.

As such I propose an addition to the AI risk debate, The PKD Test, which consists of the following question: are people genuinely frightened of AI warping humanity rather than simply destroying humanity? As long as the answer remains ‘no’5 we probably don’t have to worry overmuch about about either fate.

Dick died in March 1982, three months before Blade Runner opened6; a year which, in retrospect, marked the birth of the cyberpunk era.

4. Cyberpunk and The Singularity

Cyberpunk was a cultural movement spanning literature, film/TV, games, music, and more, which merged ‘classic’ science fiction with phildickian human/machine intermingling. But that wasn't its primary innovation.

Cyberpunk also reinforced PKD’s notion of a world of techno-animism. William Gibson’s hackers begin his Sprawl Trilogy by writing software to carve their way through ‘cyberspace,’ but by the end, they “make deals with things.” Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash is a computer virus and a biological virus, encoded as a bitmap that can infect people. “ Pat Cadigan’s ‘Pretty Boy Crossover’ declared “First you see video. Then you wear video. Then you eat video. Then you be video.”

Perhaps most importantly, though, cyberpunk was about software. Science fiction tropes hadn’t changed much fot the past fifty years. Here’s a 1931 list of them from pioneering SF author Clare Winger Harris:

You’ll notice superintelligence was already old hat in 1931. But cyberpunk introduced superintelligence as software, not androids / robots / mainframes. Today we take that lack of physical form for granted ... but software was a really weird innovation!7

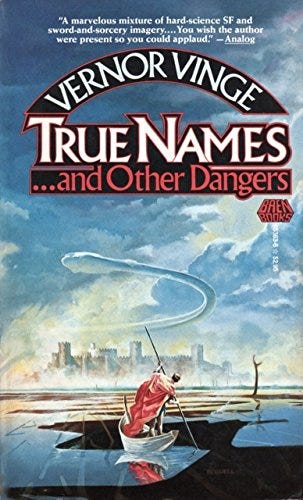

In 1981, Blade Runner was in production; Gibson was working on his first seminal short stories; …and Vernor Vinge published his revolutionary “True Names,” in which an AI erupts onto the Internet from ... somewhere ... as pure software, distributed across hijacked servers.

“True Names” was the real birth of modern AI doom, a huge shift in how we thought about it. There were prophetic forebears — Murray Leinster, Thomas Ryan, Stanislaw Lem — but “True Names” was most influential.

Vinge — a professor of computer science — also popularized John von Neumann's notion of The Singularity, the point at which technological progress goes hyperbolic, utterly transforming humanity and our world. (Also known as “The Rapture of the Nerds.” AI doom is essentially a dark Singularity, “The Inferno of the Nerds.”)

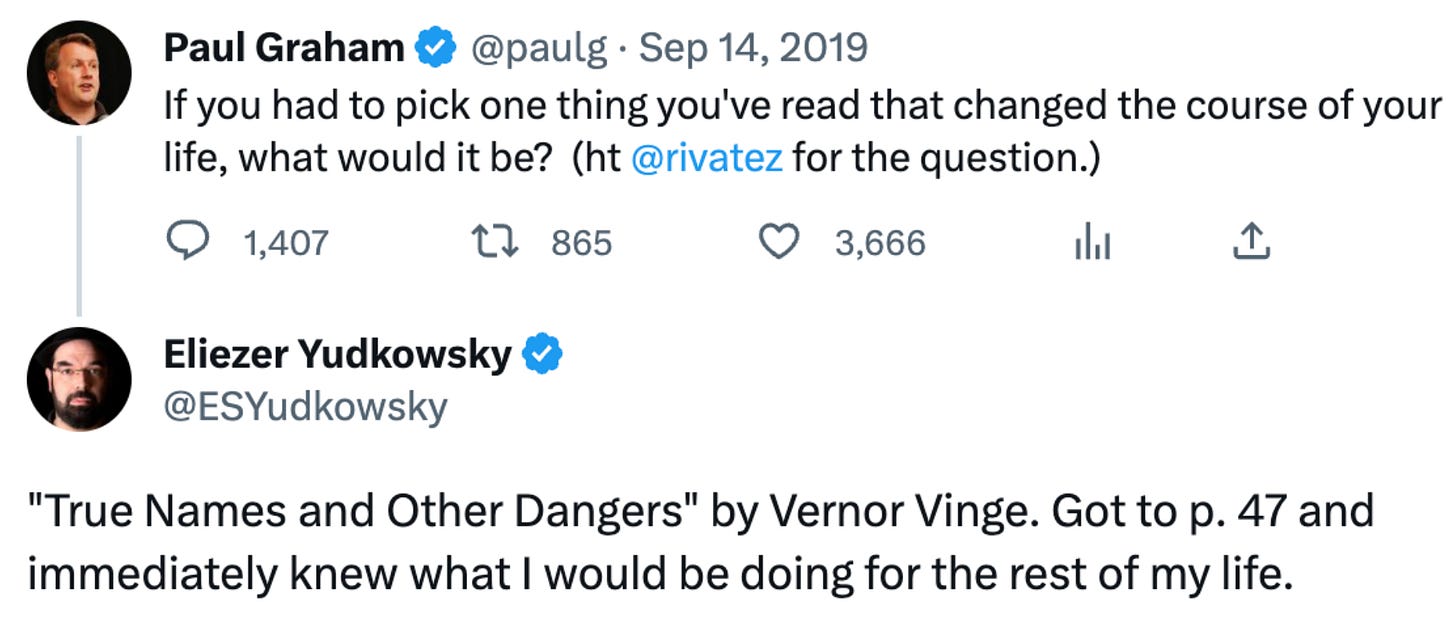

We live in the Vinge future as much as we do the PKD future. That may sound a little hyperbolic itself: after all, today only a tiny hardcore of real SF fans know of Vinge and “True Names.” Am I perhaps overstating its impact? Maybe…

…but then again, maybe not8.

5. Extropian Eschatology

If the above screenshot means nothing to you, I encourage you to segue to my series Extropia’s Children, which is about how rationalism, effective altruism, modern AI philosophy, and even (arguably) cryptocurrencies were all birthed from an obscure 90s mailing list. But I suspect most readers will be semi familiar with that backstory, and the rise of AI doom from a ridiculous fringe belief to — well — where we are now.

Three takeaways I’d like to leave you with:

We are a doomer species. No, I mean, really a doomer species. We are obsessed with eschatology. Essentially every human religion goes on at enormous length about the inevitable end of the world which just might happen in our lifetimes. Yes, even Buddhism.9 This does not invalidate any concerns re / prophecies of AI doom ... but it should be taken into account when considering them.

That said, less doomery cultures do exist, e.g. Japan, whose science fiction is historically more concerned with AI civil rights than AI doom.History was weird. The future will be too. I mean, just this cultural history of AI doom involves Indonesian volcanoes, transhumanist saints, Egyptian blood feuds, a misplaced android head, Harry Potter fanfic, and the bizarre rise & collapse of FTX. That's weird! As such we can be very confident the future will be even weirder; our world is more interconnected, breeding more emergent properties, and modern AI is already super 🤯.

This probably does invalidate all nonweird prophecies/predictions.The PKD test may be relevant. AI won't be genuinely dangerous until people are at least as scared of it warping humanity as they are of it destroying humanity. Irrevocably warping (some) humans—our bodies, minds, and/or senses—would be much easier than an apocalypse, and could well happen at our request. But that prospect is more concrete and falsifiable, and less eschatological, so we have a more accurate sense of its imminence.

As long as we're not scared of that, we shouldn't be scared of imminent AI x-risk.

Geoengineering: it works!

Did it lead to doom? Well, you’ll notice there aren’t any titans around any more…

It's also an proto-cyberpunk manifesto of sorts, discussing the first phone phreaks, and the forthcoming battles of hackers vs. the surveillance state, way back in 1970.

In fact, PKD sometimes claimed not just that our world is a Matrix-like simulation, but that the real world is the 1st century AD!

Two years ago I wrote “Granted, AI girlfriends may be the canary in that coal mine,” but that doesn’t seem to have happaned.

He did see a rough cut, and liked it.

See for instance Stephenson’s “In the Beginning … was the Command Line.”

Yudkowsky's father was very active in science fiction fandom. In fact at one point signs on the front door of their house identified it as the ‘Martian Government-in-Exile.’

“All religions contain an eschatological dimension ... In Christianity, however, eschatology plays such an essential role that, without the eschatological dimension, Christianity loses its meaning.” [...] “In India, history is cyclical ... although presently mired in the misery of the kali yuga, we should anticipate an end to this period and a return to the glorious satya yuga.” [...] “A bodhisattva named Maitreya will appear and rediscover Buddha, and the ultimate destruction of the world will then come through seven suns.” –Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev et al.

I read Valis and other gnostic PKD books in the mid oughts and found those ideas utterly captivating. I agree there's something strangely attractive about the idea of hidden reality created by super intelligent beings, that I can't quite put my finger on. (And it sure scared the heck out of 12th century Catholics!)