Here Come The Drones

Little darling, I see a disconcerting future.

But The FPV Won’t Let Me Be

All war is drone war now. In Ukraine, “Experts estimate that drones of all types now contribute to about 70% to 80% of military casualties on both sides … the general confirmed that Ukraine was deploying [fiber optic drones] with ‘a kill range of 20km’.” In Haiti, “Recent weeks have seen reports of a series of suicide drone attacks, targeting gang bosses who live deep in Port-au-Prince’s maze-like shantytowns, surrounded by barricades and guards. ‘With kamikaze drones we can reach places police officers can’t go’.” Israel vs. Iran. Armenia vs. Azerbaijan. Sudan. Myanmar. Gaza. Yemen. Libya. Mexico. Wherever you find conflict nowadays, you find God on the side of the better drones.

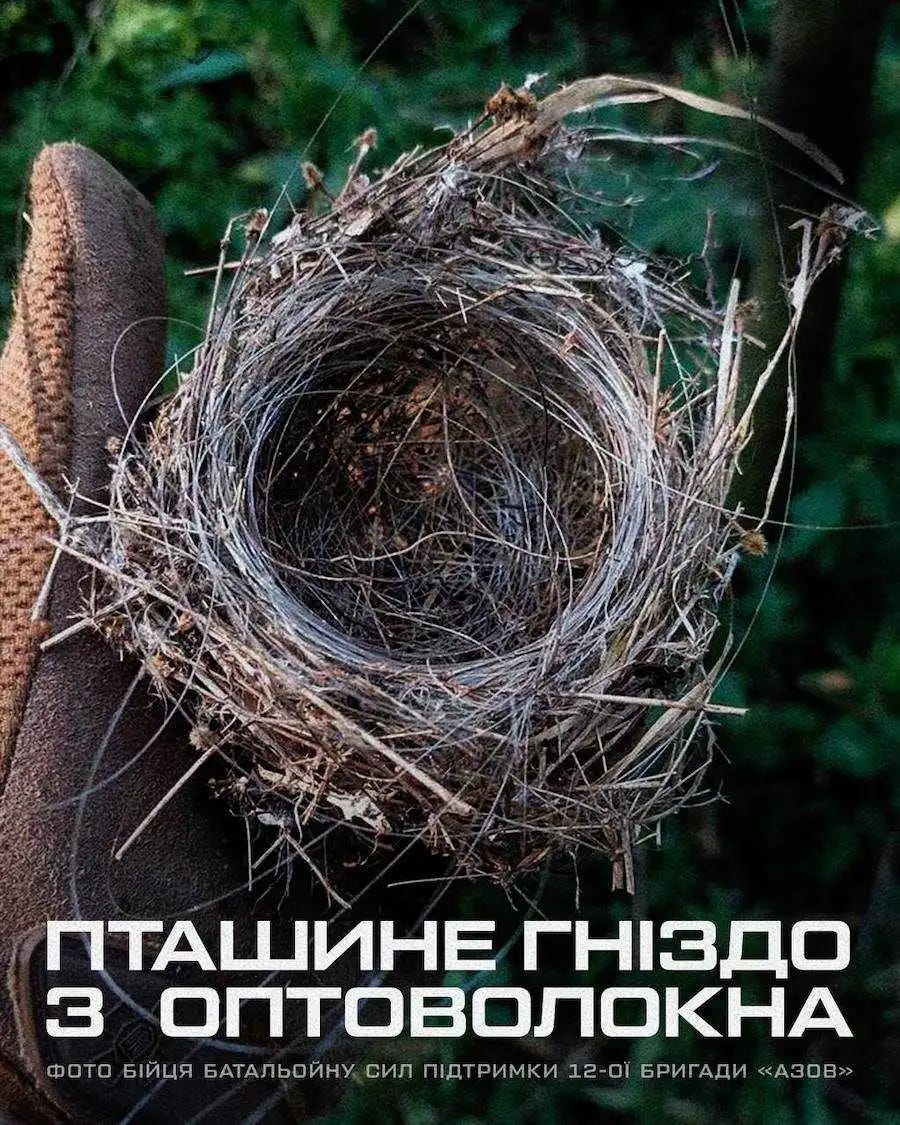

With drones come anti-drone countermeasures. First, FPV (first-person view) drones were piloted by humans against targets. Then those targets started jamming the FPV radio signals. Then counter-countermeasures: the FPV drones were tethered by fiber optics extending for many kilometers, sometimes from larger drone “mother ships” … or simply made unjammable by using onboard AI. (The front lines are now so draped with strands of fiber that birds make nests from it.) AI navigation was reportedly used in the spectacular drone attacks on airbases deep inside Russia last month.

Are you not unsurprised? I am very unsurprised. I predicted much of this fifteen years ago—more on that below—and I continue to argue that even a kamikaze drone is not just a weapon, but a node of an enemy network. As the onboard AIs get ever smarter and ever more efficient, drone swarms will become networks that act in concert, perform reconnaissance for one another, attack in dynamic waves so as to exhaust anti-drone defenses … and make these kinds of collective tactical decisions on the fly, autonomously. Such are the pitiless demands of warfare.

Of course this assumes onboard AIs will rapidly get smarter and more efficient. Are we sure that will happen in these very constrained computing environments? I’m afraid that the answer is: “Pretty sure, yep.”

Waymo’ Data, Waymo’ Problems

Is a Waymo a drone? Well. It’s not not a drone. It certainly makes extensive use of sophisticated AI. And they recently published a super interesting blog post, “New Insights for Scaling Laws in Autonomous Driving”, which reports:

Our research confirms that, similar to language modeling, increased data and compute resources can enhance the performance of autonomous vehicles. These insights benefit not only the Waymo Driver but also have broader applications in embodied AI research…

Similar to LLMs, motion forecasting quality also follows a power-law as a function of training compute. Data scaling is critical for improving the model performance. Scaling inference compute also improves the model's ability to handle more challenging driving scenarios. Closed-loop performance follows a similar scaling trend. This suggests, for the first time, that real-world AV performance can be improved by increasing training data and compute.Our findings are translatable to similar robotic planning tasks where researchers can now have a clearer sense of the data they need to collect and sizes of models that they should be training. Our research opens up the possibility to devise more adaptive training strategies for planning tasks in robotics, such as adapting the compute needed to solve more complex scenarios.

That last paragraph is very exciting! …unless you’re in the midst of violent conflict and you start thinking about it in terms of attackers coming after you with drones, in which case you’ll find it rapidly becomes the very bad kind of exciting. Consider this recent Guardian report:

This “mothership” travelled 200km into Russia before releasing two attack drones hanging off its wings. Able to evade radar by flying at a low altitude, the smaller drones autonomously scanned the ground below to find a suitable target, and then locked on for the kill.

There was no one on the ground piloting the killing machines or picking out targets. The robots, powered by artificial intelligence, chose the undisclosed target and then flew into it, detonating their explosive load on impact. The reusable mothership and its killer offspring cost $10,000 (£7,500), all-in. It can travel up to 300km, with the suicidal attack drones able to fly a further 30km.

It goes on to quote the Ukrainian CEO of a robotics company:

“All these checks that we are going through in airports are completely useless already, so we are just wasting our time. You don’t need to bring a bomb to blow up the plane. You can just wait outside with the drone and wait for the plane.

“You can just fly into an airport, 100 drones, 1,000 drones, in automatic mode. Those drones will not be afraid of the jamming, so all your protection, which does not involve physical destruction, are useless. Would you put a remote weaponised station for every airport to shoot them down? What would be the budget of such projects?”

A Prophet Is Without Honor On His Own Substack

Way back in 2009 I wrote a novel about exactly that kind of drone terrorism — drones as autonomous, AI-driven, FPGA-powered nodes of enemy networks — called Swarm. Of the nine books I count as “published,” it’s the only one I self-published … partly as experiment, partly because traditional publishers deemed it too science-fictional to be a plausible thriller, & too thriller-y to be science fiction. (Well, that’s what they said. The Great Recession didn’t help. Am I bitter? I’m a little bitter.) It’s a reminder of how incredibly implausible the rise of autonomous drones seemed even fifteen years ago.

In 2017 I wrote a TechCrunch column called “Dronerise: gradually, then suddenly”:

Drones feel a bit like old news already, don’t they? … One might well ask: what became of all that hype? Most profound technological change happens “gradually and then suddenly,” to quote Hemingway on bankruptcy in The Sun Also Rises. The question is, how do you know when you’re at the knee of the curve? When does gradually turn into suddenly?

There is reason to believe, when we look at the accelerating pace of the drone news of the last few months, that 2017 is the year that drones really begin to, well, take off… But consumer drones will remain toys for the foreseeable future. The big important drone market, the one to watch, is enterprise / industrial drones — which, in turn, will be heavily affected by regulation.

I underestimated the friction of regulation. Instead, as it turns out, dronerise was led by the military market, which doesn’t happen much with modern technology. And the military continues to be the vanguard (well, as far as we can tell) though it is worth noting that in China, “Meituan is pioneering the use of delivery by autonomous vehicles and drones, which it says have completed 4.9M and 1.45M customer orders respectively.” But in large part this is worth noting because of what it implies about China’s military drone capabilities, if and when “Taiwan” is added to the list in this post’s lead paragraph. Per The Guardian again:

A Pentagon programme known as Replicator 1 is due to deliver “multiple thousands” of all-domain autonomous systems by August 2025.

A first mission is reportedly imminent for the Jiu Tian, a Chinese mothership drone said to be able to fly at 50,000ft (15,240 metres) with a range of more than 4,000 miles (6,400km), carrying six tonnes of ammunition and up to 100 autonomous drones.

As such my history of drone prophecy is a mixed bag, in that my apparently wild and crazy notions of coordinated AI-powered drone kamikaze assaults on faraway targets have come true, whereas my reasonable conservative predictions of widespread commercial drone delivery in rural areas have completely failed to happen. It might be worth pondering briefly whether this itself is a meta-prophecy … such that, when it comes to drones, the most kinetic visions are those most likely to rapidly come true.